Thus far the most important thing I’ve learned in my PhD is that research is HARD, especially when you are working with human subjects. Although I am not working with people directly, I am doing research with electronic medical records in a database that encompasses over 74 million people! The possibilities are thrilling, but I’ve had to learn how to work within the means of this system. Medical records and diagnostic coding were created for insurance purposes, not research. This is something I need to constantly remind myself of.

Additionally, when working with humans, you can’t control for everything! Humans are not in a cage receiving the same food, water, and environment everyday. Extra variables you aren’t planning on studying but may affect your outcome are called confounding variables. Although these are almost impossible to avoid entirely, it is the scientist’s job to try to control for as many in the best way that they can. It is also their job to acknowledge these variables in publication so you present an accurate depiction of your work.

In my first nine week rotation, I have been working on my own research project. This has been rewarding and frustrating at the same time. During my weekly meetings with my advisor I get constant feedback and new variables are brought to my attention. Have I considered this confounding variable? Am I too deep in a topic and need to focus instead on a larger picture? What is my main goal? I even had to change my topic three weeks into the rotation. Feedback is constant during a PhD and although I highly appreciate it and believe it is the only way to improve, sometimes it can be challenging. Sometimes I have to remind myself that this is not a doubt in my skills or ability but instead just an opportunity someone is giving me to grow.

Currently, I am performing a descriptive study comparing Type 1 and Type 2 diabetic retinopathy which is a leading cause of blindness worldwide. I hope to take this idea further and get into the weeds of the topic, but by doing so, I am starting to run into more and more confounding variables. So here is the question: When performing an ecological study where confounding variables are inevitable and challenging to control for, what is the value in the study?

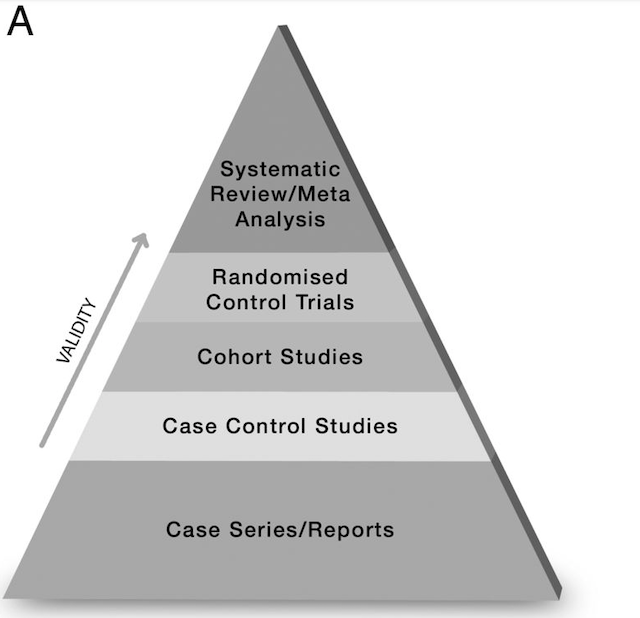

For me, these studies are not perfect and conclusive science. In fact, when you look at the research design hierarchy displayed below you can see that case studies are at the bottom of the pyramid. Ecological studies are located just above them. Although these studies are inconclusive and not the gold standard of research, such as randomized control trials, this does not mean they lack value. Instead they are a starting place to begin a conversation. Yes these studies will get hit with criticism stating their flaws, but at least they’re opening up a conversation and therefore the possibility for more research to be done.

“Research is not about the single publication, but about a discussion between papers” (from the European Society of Endocrinology Talks). I love this quote. It reminds us that research should not be about competing against each other, but a collaborative environment. By publishing even a rudimentary study discussing population health, this exposes a new idea that people all over the world now have access to. Now the real work can begin and stronger tests conducted! If this pandemic taught science anything, it is the need for us to collaborate and share our work with each other so we can help the most people possible.

When I hopefully present or publish my work on diabetic retinopathy, I cannot tell you for certain that I found a new relationship, but I can tell you that I found something interesting. Something that may not have been discussed yet and this finding deserves a discussion. When we are talking about our country’s health, is any conversation too small to explore?